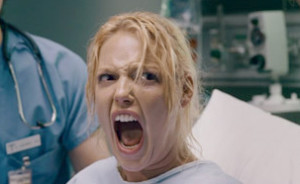

For centuries, birth has terrified us. Everything in our culture, including scenes from movies and television shows, portrays and reinforces our fears, and then soothes us with the promise of salvation through birth technology — epidurals, Pitocin drips, fetal monitors, episiotomies, and C-sections. Ironically, our U.S. infant and maternal mortality rates are some of the highest in the developed world.[i]

For centuries, birth has terrified us. Everything in our culture, including scenes from movies and television shows, portrays and reinforces our fears, and then soothes us with the promise of salvation through birth technology — epidurals, Pitocin drips, fetal monitors, episiotomies, and C-sections. Ironically, our U.S. infant and maternal mortality rates are some of the highest in the developed world.[i]

The fear of mothers dying in childbirth is nestled deep in our shared cultural psyche, and right behind it is the fear of giving birth to a dead baby. Both of these do occur, but extremely rarely. Nonetheless, childbirth and death have been unjustifiably entwined in our collective unconscious for many centuries; just think of all the legends, fairy tales, and movies featuring “The mother died in childbirth.”

This fear of dead mothers and dead babies has been conflated into vague and not-so-vague fears of the birth experience itself, and in an age when we have eradicated so many other fears it would seem self-evident that we could tame our birth demons through research and technology. But we set off to do so with one gloved hand tied behind our back, so to speak.

The field of obstetrics rests on a younger foundation of research evidence than do other medical specialties. The gynecological territory of the female anatomy in general was the poor stepchild in the world of medical research a couple hundred years ago, and obstetrics was particularly neglected, since pregnancy was the awkwardly prominent evidence that a woman had <gasp> engaged in sex, which was taboo. We painted ourselves into a medically ignorant corner with our cultural sanitization of pregnancy (as in, “She’s expecting”).

Birth Technology Follows the Money, not the Mother (or Baby)

In the mid-20th century, atop our pretty meager understanding of birth physiology came the desire of hospital administrators for cost efficiency in tending to laboring patients. In 1955 arose the notion of “active management of labor” when Emmanuel Friedman developed the partograph — a chart that allowed obstetrical attendants to determine whether the progress of their patients’ labor conformed to an ideal mathematical curve: the infamous yet all-hallowed Friedman’s Curve.

Labors that lagged behind the ideal could be made to keep the prescribed pace with the use of oxytocic drugs (such as Pitocin, a synthetic form of the body’s own oxytocin, the hormone of human connection and contractions). Friedman’s Curve is designed to help physicians keep labor advancing along a “normal” route. A woman who fails to fall in step is considered to be having an “abnormal” labor, which can be made “normal” again with Pitocin. Feminist author Alice Adams sees this as chillingly similar to  the “disciplined and docile bodies” in sociologist Michel Foucault’s analysis of military regimentation.

the “disciplined and docile bodies” in sociologist Michel Foucault’s analysis of military regimentation.

Electronic fetal monitoring (EFM), Pitocin induction, and cesarean section were designed for use in a very small number of cases, when extraordinary measures were called for (and they are indeed a blessing in this small percentage of cases). But once the equipment was bought, paid for and sitting in relative disuse, there came the irresistible impulse to begin using it routinely, for all pregnant women and in all births, which is where the trouble began.

Monty Python‘s send-up of this whole situation would be hilarious if it weren’t so eerily spot-on — not just the birth technology but the attitude to the mother, whose question, “What do I do?” is answered, “Nothing, dear — you’re not qualified.”

Routine use of the machine that goes ping (EFM) was begun in the 1970s, even though there was no proof of its clinical effectiveness. EFM has in fact never been shown to do what it set out to do, which was to improve birth outcomes. In 1987 the prestigious medical journal Lancet reported that the routine use of EFM “had no measurable effect on death or illness of infants or mothers” and even worse, that it “was associated with a higher rate of Cesarean deliveries, which increases surgical risks to mothers.”[ii]

Yet twenty-six years later, in the absence of any new evidence to contradict this damning conclusion, the vast majority of births in America involve electronic fetal monitoring. And in response to the obvious question, “If EFM doesn’t work, why haven’t obstetricians abandoned it?” birth educator and author Henci Goer notes that doctors and hospital administrators aren’t exempt from our cultural fascination with high tech equipment. They are as susceptible to slick marketing of the latest innovations as any other gadgetry enthusiast: “EFM is expensive, scientific, and complicated. It simply had to be better than putting a stethoscope or even a Doptone — the little hand-held ultrasonic device — to the tummy.”

So we as consumers need to ask ourselves if we are as enthusiastic about birth gadgetry. (I have to wonder how many of you — like myself when our son was born in 1987 — realize that the internal form of EFM requires that an electrode, in the form of a tiny screw, be stuck into your baby’s scalp?) Some think that our loving embrace of EFM taps into our 21st century delight over anything we can see on a screen or a monitor!

Finding & Honoring Your Own Pace

Whether birthing at home or in a hospital or birth center, it helps to understand what facilitates labor and what can arrest labor. Obstetrician and researcher Michel Odent suggests that the best way to join forces with birth is to remember that we are mammals, and the need of all mammals to birth smoothly and successfully is the same three things we (like other mammals) require to fall sleep: safe privacy, quiet, and low light.

The most common way to disturb birth is to do too much talking (even the most supportive “coaching” affirmations). When the neocortex (the area of the brain that processes language) is engaged, many aspects of the physiologically brilliant birthing process are blocked. Why? Because thinking actually requires adrenaline, which prevents the necessary levels of oxytocin required to dilate the cervix. How many cases of “failure to progress” (i.e., casualties of Friedman’s Curve) are caused simply by too much talking, even the most well-meaning of inquiries such as “How are you doing?”

I mean, imagine you’re trying to fall asleep, and your partner — even in the most loving, whispery, “supportive” way — were to start saying, “You’re doing really good, hon…how it is feeling, are you almost asleep?” Instead, a partner’s true task is to cocoon the laboring mother from phone calls, texts, tweets, visitors, and all other contact — anything that is characteristic of the “modern human” (especially lights and language). All such stimulation brings adrenaline to your system and can put the brakes on labor.

Your higher thinking centers need to be “excused” from the situation, and you need to be allowed to go to that inner space of your deepest primitive callings, where your bodymind’s instinctive knowing can do what it knows how to do — birth your baby!

If you do find yourself leaning into the siren call of technology, remember that the Parenting for Peace principle of simplicity presides over birth in a way that is evidence-based: the governing bodies of the professional obstetrical societies in both the U.S. and Canada have found that intermittent listening with a handheld device is as or even more effective than electronic fetal monitoring.[iii]

More Ideas for EMPOWERing Birth coming next…

EFM image by miguelb, used by its CC license

[i] Datablog. “Maternal Mortality: How Many Women Die in Childbirth in Your Country?” Guardian.co.uk, http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/2010/apr/12/maternal-mortality-rates-millennium-development-goals. The U.S. ranks an abysmal 41st on the World Health Organization’s list of maternal death rates, behind South Korea and Bosnia—yet we spend more money on maternity care than any other nation; Friedman, Danielle. “Why Are So Many Moms Dying?” Daily Beast, http://www.thedailybeast.com/blogs-and-stories/2010-03-24/why-are-so-many-moms-dying/.

[ii] Prentice, A. “Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring During Labour: Too Frequent Intervention, Too Little Benefit?” The Lancet 330, no. 8572 (1987): 1375-77.

[iii] Gaskin, Ina May. Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth. New York: Bantam-Dell, 2003.

Tags: birth technology, C-section, childbirth history, EFM, fetal monitor, Friedman's curve, infant mortality, maternal mortality, socio-cultural